April 2nd, 2021 • Joshua Manson and Liz DeWolf

The Federal Bureau of Prisons Is Even Less Transparent Than We’d Thought

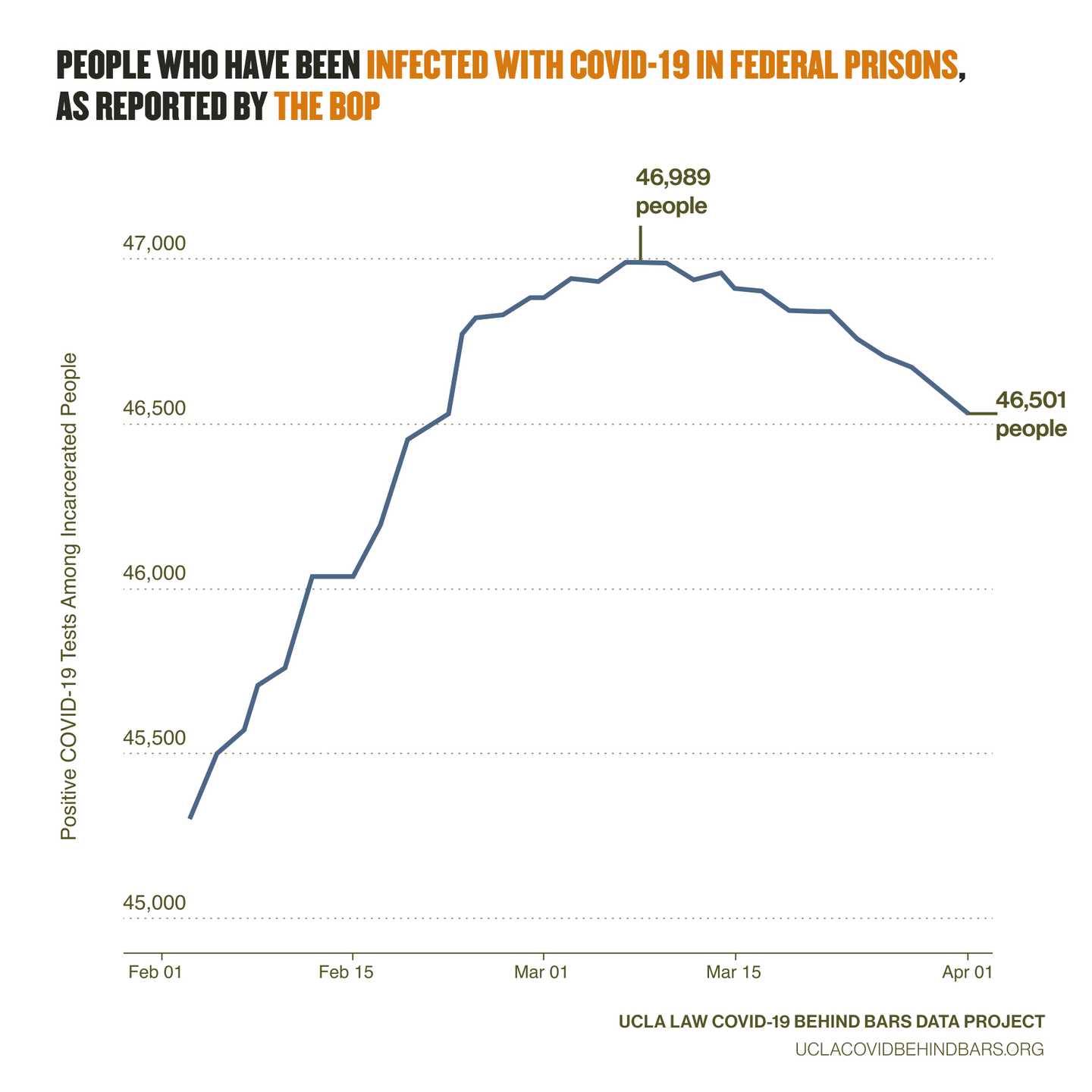

In early March, nearly one year after the first COVID-19 death in the federal prison system, the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) reported that there had been a total of 46,989 cases of COVID-19 among people incarcerated in federal facilities since the start of the pandemic. That number is staggering, though not exactly surprising given that social distancing is often impossible in prisons.

What is surprising, however, is that in recent weeks, as noted by the Marshall Project, the BOP has reported a decrease in that sum — an illogical trend for a number that presumably can only increase over time, as more tests come back positive. As of this writing, it stands at 46,501.

When we reached out to the BOP for an explanation, a spokesperson informed us that the drop in reported cases was not, in fact, an error. Rather, it was the outcome of an intentional reporting choice. According to the spokesperson, throughout the pandemic the BOP has been removing cases from its total count whenever a person who previously tested positive is released from custody. While the definition of the COVID-19 cases variable on the BOP’s own dashboard (“number of inmates that have ever had a positive test”) suggests the agency is reporting cumulative cases among those who have been incarcerated during the pandemic, it actually reports cases only among those currently incarcerated.

This reporting practice is disturbing because it obscures the true toll of the coronavirus in federal prisons. Without a true cumulative case count, it is extremely difficult for observers to track the incidence rate — the rate over time — of COVID-19 infection among the federal prison population. This incidence rate is important for understanding the risk of infection that individuals face while incarcerated and for evaluating the BOP’s response. With the BOP’s data as reported, we can only calculate “point prevalence” — the infection rate among the population at a specific point in time.

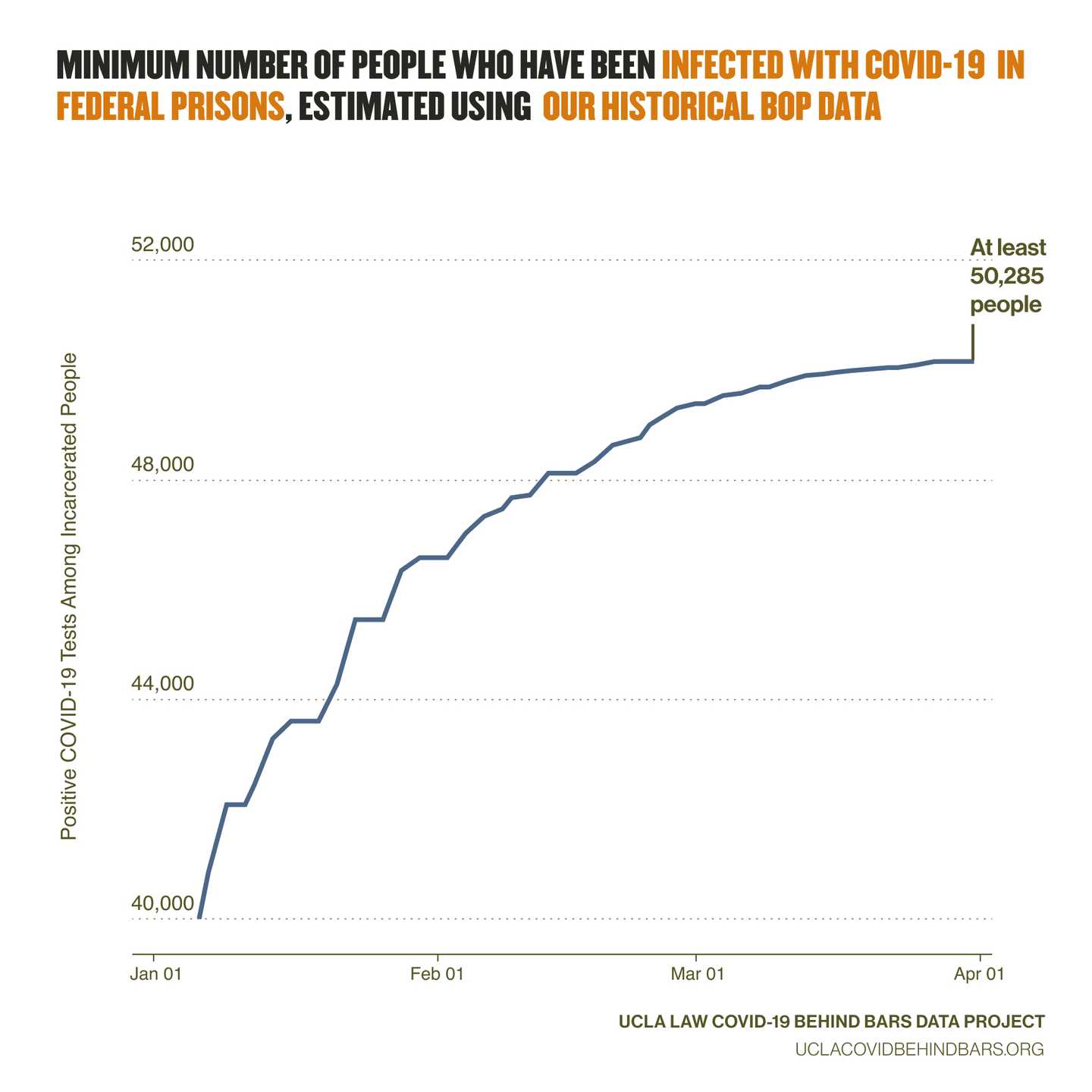

A close analysis of the historical facility-level data we’ve collected from the BOP’s dashboard indeed shows that dozens of BOP facilities have removed cases from their total counts almost every day since at least as far back as October 2020. This went undetected for so long because, until recently, there were so many new infections in federal prisons — and so few releases — that the number of new cases across the BOP system still outpaced the number of cases removed, resulting in a consistently upward trend systemwide.

Using that historical data, we estimated that the minimum number of cases over time across the federal system is at least 50,285 across all facilities — still undoubtedly an undercount of the total number of people who have had detected COVID-19 infections in federal prisons, but a number closer to the truth than the just over 46,000 cases currently being reported.

In March, when we released our scorecard grading each state and federal prison system on its COVID-19 data reporting and quality, we gave the BOP credit for reporting cumulative cases in line with our definition: the number of people who have ever tested positive for COVID-19 while incarcerated. Having discovered that the BOP does not report this variable as we define it, we’ve adjusted the agency’s score downward. As a result, the BOP’s grade dropped from a D to an F.

Although we know the BOP’s data are flawed in the manner described here, we will continue to share facility-level data on our website as published on the BOP dashboard, because these are the only data available.

While looking into this issue, we noticed another perplexing pattern on the BOP’s dashboard: facility-level variables do not always sum as expected. For example, since the BOP removes people who have been released from its data, the total number of cases at each facility should match the combined totals of people currently infected, those who have recovered, and those who have died from the virus. However, for some facilities, the total number of cases is much lower than the combined total of active infections, recoveries, and deaths. For example, the BOP reports that there are 1,111 people currently incarcerated at Beaumont Low FCI in Jefferson County, Texas who have recovered from COVID-19, but at the same time reports that there have only been 660 detected infections at that facility. It is therefore unclear whether the BOP adjusts total cases (and other variables) when transferring people who have been infected between its facilities, and whether it treats all variables similarly with respect to those who are infected and then released. In our communication with the BOP, the agency ignored our question about why the facility numbers don’t add up.

These data errors are particularly troubling not only because the BOP has so many people in its custody (currently more than 125,000) and has managed the pandemic so poorly, but also because it may serve as a model for state prison systems. Although the federal government does not have direct control over state prison agencies, the BOP is often heralded as an example for other jurisdictions to follow, especially in implementing reforms. When the BOP manipulates its own data and is not held accountable, it sends a message to state agencies that they can do the same.

We call on the BOP to release the historical data showing the number of people who have ever tested positive for COVID-19 while incarcerated in its facilities, regardless of current incarceration status. In the meantime, we continue our mission to aggregate and share officially reported COVID-19 data about carceral facilities with transparency and integrity.

Data analysis by and support from Erika Tyagi and Neal Marquez.

next post

April 7th, 2021 • Sharon Dolovich and Poornima Rajeshwar

SARS-CoV-2 Variants go to Prison: What Now?

In the last two months, the presence of SARS-CoV-2 variants has been reported in three prison systems. The variants are more contagious and can accelerate viral spread. To avoid a corresponding increase in infections and deaths, corrections officials must adopt a multi-pronged strategy of regular testing, vaccination, and decarceration.