April 15th, 2021 • Poornima Rajeshwar and Erika Tyagi

Vaccine Hesitancy Behind Bars: Causes and Concerns

For over a year now, COVID-19 has been raging through federal and state prisons and jails, causing widespread infections and fatalities among staff and incarcerated populations. In the absence of proactive mitigation efforts such as mass releases, mass surveillance for infections, adequate personal protective equipment and sanitary living conditions, much now hinges on vaccine administration in these high-risk settings.

Achieving population immunity in carceral facilities by vaccinating as many people as possible is critical to abating viral spread. However, as we’ve previously documented, there has been a troubling lack of political will to ensure meaningful vaccine access for incarcerated people. To complicate matters still further, vaccine access alone is insufficient; achieving facility-wide herd immunity will also require broad vaccine uptake among incarcerated people as well as correctional staff.

A recent report published in Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report (MMWR) highlights concerns around vaccine hesitancy among the incarcerated. The report, co-authored by members of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the UCLA Law COVID Behind Bars Data Project, is based on survey data collected in three prisons and 13 jails across four states. The survey was led by the University of Washington’s Dr. Marc F. Stern, a nationally-recognized expert on correctional health and the lead author of the MMWR report. (Co-authors include Alexandra Piasecki, Priti Patel, Rena Fukunaga and Nathan Furukawa from the CDC COVID-19 Response Team; Poornima Rajeshwar, Erika Tyagi and Sharon Dolovich from the UCLA Law COVID Behind Bars Data Project; and Lara Strick at the University of Washington and the Washington State Department of Corrections.)

Data were collected between September and December 2020 (largely before the FDA issued emergency-use authorization for the first COVID-19 vaccine) and included 5,110 participants. Participants were asked whether, once a COVID-19 vaccine is authorized for use, they would be willing to receive it. In response, 45% of the survey participants expressed an initial intention to accept the vaccine if offered (“yes”), 45% said they would refuse (“no”), and 10% were undecided (“maybe”). The authors determined that willingness to receive a vaccine was lowest among Black participants (37%), incarcerated people between the ages of 18 and 29 (38%), and those held in jails versus prisons (44%).

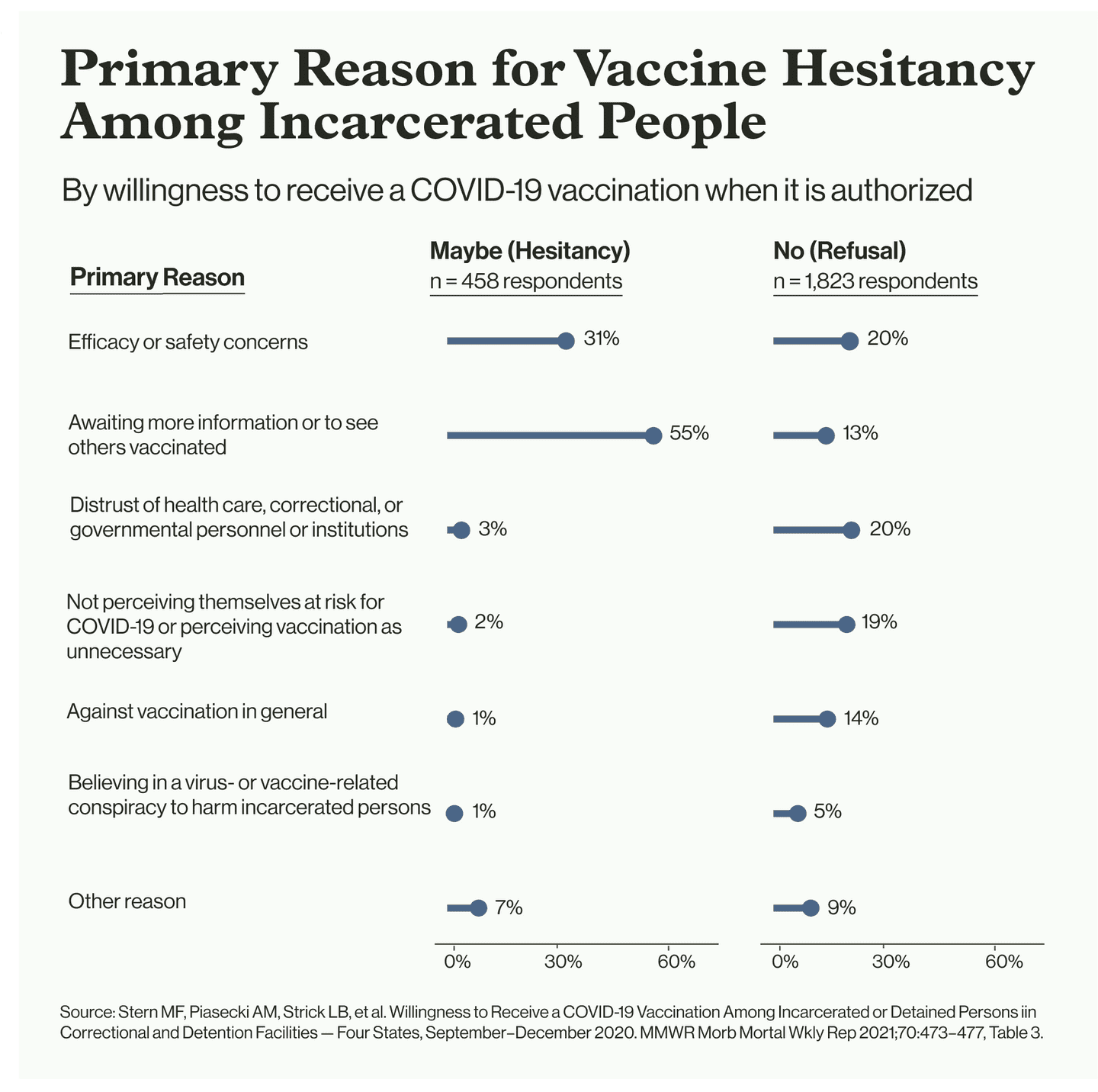

For those respondents who answered “no” or “maybe,” survey administrators followed up with an inquiry about reasons. Among those who answered “maybe” and provided a reason, 55% wanted more information or were waiting to see others vaccinated, and 31% were concerned about efficacy or safety. Of those who said “no” and provided a reason, 20% expressed distrust of the carceral and public health systems, 20% were concerned about efficacy or safety, and 19% thought vaccination was unnecessary.

As the report points out, this data has some limitations. The facilities where the data were gathered — located in Washington, Florida, Texas and California — were not nationally representative. The survey was largely conducted before the first vaccine was approved. And stated willingness, ex ante, to take the vaccine when it is offered is not a perfect measure of whether a person will actually agree to be vaccinated when the opportunity finally presents itself. Despite these limitations, the study’s findings fall within the broader range of acceptance rates that have been reported in other jail systems. For example, only 40% of inmates at two jails in Massachusetts and 34% in the Santa Rita Jail have accepted the vaccine.

On the other hand, several state prison systems have seen much higher acceptance rates. Last month, the Rhode Island Department of Corrections (DOC) reported an acceptance rate of 73% among the state’s incarcerated population, while officials in Louisiana said that 80% of incarcerated people offered the vaccine had been willing to take it. After a federal judge ordered all incarcerated people in Oregon be offered vaccines in February, the DOC reported that 70% have accepted at least one dose. The acceptance rate was 86% among elderly and medically vulnerable prisoners in Oregon, as the agency noted in January. According to the director of the Oregon DOC, the high uptake rates could be attributed to their education program and opt-out policy for vaccinations. In the opt-out policy, according to the director, “Every adult in our custody was signed up for a one-on-one appointment with their health care provider to talk about the COVID vaccine. And at that point they were either given the dose or they affirmatively decided not to get the vaccination.”

As reporting from The Marshall Project highlighted, another motivating factor for those taking the vaccine behind bars may be the desire to return to “normalcy” after a year of lockdowns, where in-person visits, college classes, and treatment programs have ended. Several systems, such as the Cook County Jail, have recently announced that they will resume in-person visits for detainees who are vaccinated — providing a further incentive to accept the vaccine despite reservations.

Correctional staff have been prioritized in most jurisdictions since the beginning of vaccine distribution. Despite the assured access, staff uptake rates in many prisons have been dramatically low. Illinois recorded a staff vaccination rate below 30%, and less than half of correctional staff in Massachusetts, West Virginia, Iowa and Oregon have accepted vaccines. (Many agencies, such as the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), don’t require staff to report vaccinations from community healthcare providers, making it impossible to know true staff vaccination rates.)

Historically, vaccine hesitancy has been a concern in the face of infectious diseases. Current times are no different. In the context of the present pandemic, some common reasons for hesitancy include genuine concerns related to the side effects and efficacy of the vaccine. But a worrying trend has also involved myths and misinformation about COVID vaccines in carceral institutions and in the general population. A closer look at Stern’s survey data offers insight into common misconceptions and concerns.

Stern’s data show that several individuals considered the vaccine unnecessary, believing that they had acquired immunity from already contracting COVID. Conversely, others believed that the vaccine was unnecessary because they had not yet been infected. Some respondents who expressed concern about safety and efficacy were skeptical of the emergency use approval process for the vaccines and worried that the clinical trials may have been rushed. Several individuals cited religious beliefs as their reason for refusal. Misinformation on the composition of the vaccine — for example, that it consists of a live virus — was also noted by a handful of respondents.

Distrust of the correctional system, health care providers, and the government stood out among the responses. Several respondents specifically mentioned that they did not want to be “guinea pigs,” a posture evoking the dark history of medical experimentation inside prisons. A few said that they would only take the vaccine once they get out of the system. Along these lines, nearly one in four respondents said they would rather wait for more information or see others vaccinated before they accept the vaccines.

These reasons reinforce what advocates have been saying for months: there is an urgent need for vaccine education inside prisons and jails. As the MMWR report highlights, it is important that vaccination information is “culturally relevant and appropriate for persons of all health literacy levels, and that [it] is conveyed via multiple formats and languages including video messages, handouts, posters, presentations, peer interactions, and discussions with experts.”

Some correctional agencies seem to be taking steps to address this. For example, Illinois’s DOC website lists AMEND’s FAQ document as an educational resource for its prisoners. Utah’s DOC also has a detailed FAQ document addressed to incarcerated people. Mississippi was among the first states to set up a mass vaccination campaign for prisoners, starting with the three most populated facilities, and reported only a 1% refusal rate. According to officials, they encouraged prisoners by letting them know that staff members had taken the vaccine too. As in the case of Oregon, an opt-out policy can also be an effective way to promote vaccine uptake.

Other state agencies, like Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Louisiana, and Virginia, found themselves staring down high refusal rates among prison residents, and responded by offering incentives such as modest sentence reductions and phone-call and commissary credits.

Addressing hesitancy among staff is equally important — not only to secure their own health and to prevent further community spread, but also to promote the faith of incarcerated people in the vaccine and its providers. To encourage uptake among staff, the Colorado DOC is offering $500 to all employees who get fully vaccinated.

As noted, the single biggest driver of vaccine refusal among prison and jail residents reported in Stern’s data was distrust of the authorities. Correctional agencies need to acknowledge the understandable drivers of such distrust, which might discourage incarcerated people from participating in the vaccine program. Horror stories from Oregon of staff spreading myths about harmful side-effects of the vaccine on fertility and reports from Mississippi of correctional authorities threatening prisoners with repercussions for vaccine refusal (that the DOC proudly reported to be only 1%) indicate just how much work remains to be done.

As a first step, it is crucial that corrections administrators involve people who are respected by people in custody, including family members and thought leaders both inside facilities and from the broader community. Through pursuing this and other strategies designed to reach those skeptical about the vaccine itself or institutional motives for advocating acceptance of it, officials may yet succeed in generating the level of trust necessary if uptake rates are going to reach the point required to defeat the virus in carceral facilities.

next post

April 15th, 2021 • Joshua Manson

Data Projects Submit Joint Testimony to Congress on the Bureau of Prisons’ Mismanagement of the Pandemic in Federal Prisons

The UCLA Law COVID Behind Bars Data Project, the COVID Prison Project, and the COVID, Corrections, and Oversight Project at the University of Texas at Austin submitted joint testimony to Congress outlining failures by the Federal Bureau of Prisons to manage and report on COVID-19 in its facilities.