February 18th, 2021 • Joshua Manson

Who’s Getting the Vaccine Behind Bars?

As COVID-19 vaccines are becoming available to more and more people across the United States, one especially vulnerable population is often left behind: people who are incarcerated.

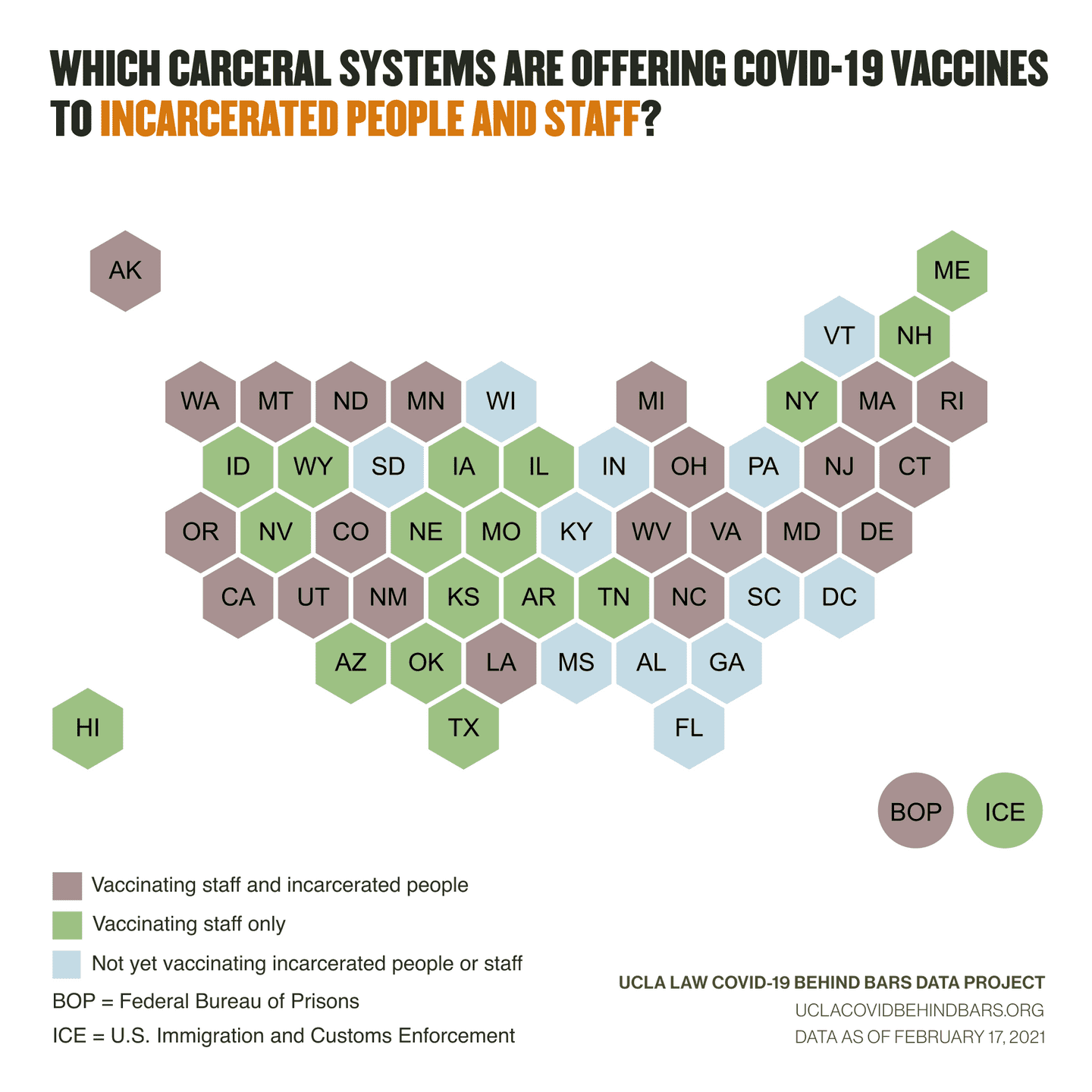

Despite calls for those living in prisons, jails, and detention facilities to receive priority vaccine access because of their heightened risks of contracting and dying from the virus, these groups appear to be receiving — or set to receive — vaccines well after their non-incarcerated peers, including those living in other congregate settings. In some cases, those living behind bars are even being prioritized after the correctional staff they interact with every day.

In Delaware, by mid-February, 867 state prison staff had received a vaccine, compared with only 95 people incarcerated in state facilities. In Colorado, 2,395 staff have received vaccinations and only 574 incarcerated people have. In Minnesota, 554 staff have received vaccines and 348 incarcerated people have.

In California, by mid-January, more than 21,000 prison staff had received a vaccine, as compared to only 3,980 incarcerated people.

In other systems, the number of incarcerated people who have received vaccines, while still low, are equal to or greater than the number of staff who have. In Ohio, 1,117 staff and 1,261 incarcerated people have. In Virginia, 13,256 incarcerated people have and 6,016 staff have. And in California, the rate at which incarcerated people are receiving vaccines appears to have accelerated since the initial rollout: by now, 34,736 incarcerated people have received vaccines and 24,776 staff have.

As for federal prisons, as of February 18, the federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) reports that 9,710 staff had been fully vaccinated, while just 7,473 incarcerated people had. While those numbers appear promisingly close to equal, that’s likely only because so many staff have themselves first refused the vaccine. And still, at a number of federal facilities, many more staff than incarcerated people have received vaccines: in FCI Elkton, which saw an explosive outbreak last summer, 175 staff have been fully vaccinated, but only 21 incarcerated people have.

Media reports have indicated that other states, though not reporting data, may be similarly prioritizing staff. The Texas Tribune has reported that every single one of the 5,562 doses that the Texas Department of Criminal Justice has administered has gone to staff, and none to incarcerated people. Arizona began offering vaccines to prison employees in January, but has still not made the vaccine to incarcerated people.

It’s important to keep in mind that in all these carceral agencies, there are several times more people who are incarcerated people than there are staff. Accounting for that disparity, every agency is vaccinating its incarcerated population significantly, disproportionally slower than they are vaccinating their staff.

That states appear to be making the vaccine available to staff much more readily than to incarcerated people, though disturbing, comes as no surprise.

In November, the BOP set a precedent when it announced that it would “reserve” its initial vaccine allocation for staff. Then, when state governments submitted their vaccine allocation plans to the CDC, many put prison staff ahead of the people incarcerated in state-run facilities. Delaware, for example, proposed that staff be included in Phase 1b, to receive the vaccine in Week 4; people residing in prisons were placed in a subsequent group, to receive the vaccine in Week 11. California initially prioritized incarcerated people in the second tier of Phase 1B, but has since abandoned that framework. In Missouri, where people incarcerated at a St. Louis jail recently took over part of the facility in protest against inhumane conditions, incarcerated people were explicitly made a bottom priority in vaccination.

In an internal memo, the BOP justified its staff-first approach by suggesting that making the vaccine available to staff would create a “wide umbrella of protection” to staff, incarcerated people, and members of neighboring communities, as staff frequently enter and leave the facility, presumably bringing the virus with them. However, it is not known whether an individual who has received a vaccine can still transmit the virus, even if they are less likely to become seriously sick with it. And in any case, because those living inside carceral facilities have no way of protecting themselves, they continue to be infected, and to die, at a rate several times higher than that of their non-incarcerated, same-age peers.

Further, where prison employees are being offered the vaccine first, they appear to be turning it down in large numbers, compounding the need for those they come into close contact with to receive it. In recent weeks, roughly half of prison employees in Massachusetts, California, Iowa, and Oregon have either refused the vaccine or indicated that they likely will.

To mitigate the outsized COVID risk facing the members of this disproportionately vulnerable group, the incarcerated should be offered vaccinations along with staff. And as a federal judge in Oregon recently wrote in a landmark opinion: The Constitution itself “imposes an obligation on [correctional departments to protect the people in their custody because they cannot protect themselves].”

Indeed, while rightly calling for prison staff to be prioritized among general population, public health experts have roundly rejected a staff-first approach in carceral facilities. On its website, the CDC encourages jurisdictions to vaccinate staff and people incarcerated “at the same time,” citing a shared increased risk of infection. In December 2020, nearly 500 public health and criminal legal experts signed onto our open letter demanding that staff and incarcerated people receive equal and high priority.

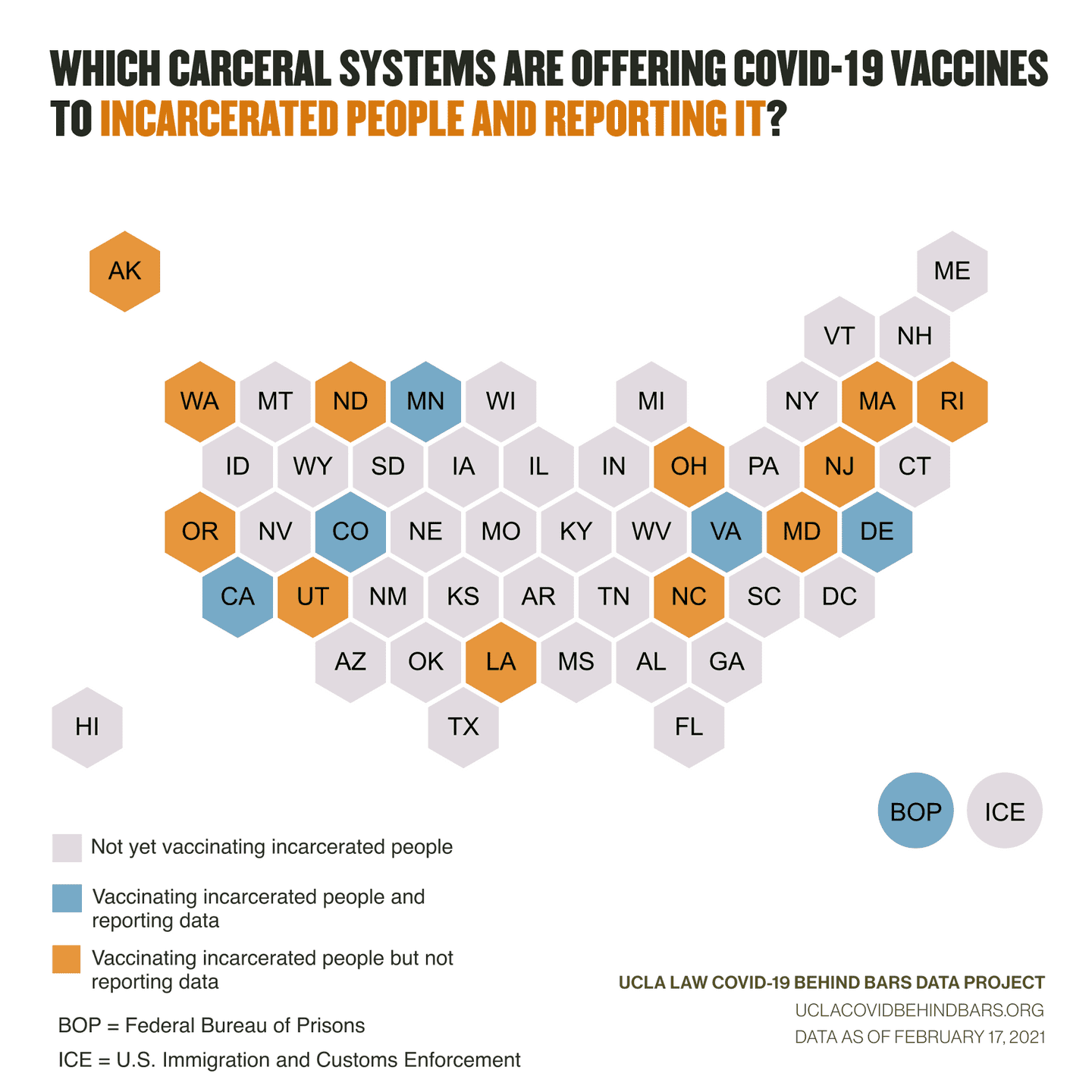

But the reality of the vaccine rollout – including delayed and deprioritized access – for people held in jails, prisons, and other detention facilities may be even more bleak than the numbers thus far reveal. In fact, at this point, it’s hard to know exactly how the vaccine rollout is unfolding behind bars, because the data is so sparse.

To their credit, at least the prison systems mentioned above are reporting data on their websites related to the vaccine rollout in their facilities. But they are as yet the only states to do so. Throughout the pandemic, carceral agencies have been slow to publish data related to COVID-19 in their facilities; as the vaccine roll-out picks up, this concerning trend appears to be continuing.

In a number of states, incarcerated people and advocates are now fighting for access to the vaccine. Earlier this month, a federal court found Oregon’s prison agency may be violating the Eighth Amendment by denying access to vaccines for incarcerated people and ordered the agency to immediately? offer vaccines to all people in its custody. In New York, where prison staff are currently eligible to receive vaccines, a group of public defenders has sued Governor Cuomo, demanding that incarcerated people also be given access.

Meanwhile, in the absence of widespread vaccination in carceral facilities, the threats posed by the likely introductions of more contagious coronavirus variants to overcrowded, unhygienic carceral facilities is growing even graver.

“A more infectious virus is only going to infect more people,” Chris Beyrer, a professor of public health and human rights at Johns Hopkins University told Vox. “If more people are going to get infected, more people are going to die.”

Last week, for the first time, the more contagious B.1.1.7, or UK, variant was identified in an American prison. An employee of Bellamy Creek Correctional Facility in Michigan tested positive for the variant; now, just a week later, at least 88 people incarcerated inside have tested positive for the variant with a hundred more results pending.

next post

February 25th, 2021 • Joshua Manson

New Analysis Reveals Devastating Toll of COVID-19 on Prison Employees

A new article published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine has found that staff of U.S. prisons are three times as likely to contract COVID-19 as the general U.S. population. The study’s authors cross-referenced data collected by the UCLA Law COVID Behind Bars Data Project with publicly available personnel data from state and federal departments of corrections to measure the scale of what they called an “unprecedented occupational hazard” for employees of American prisons.