June 7th, 2023 • Kamilah Mims, Shireen Jalali-Yazdi, Nora Browning, Joe Gaylin, Viviana Gonzalez, Mike Dickerson, and Jade Magaña

Study: Incarcerated People Faced Medical Abuse, Poor Safety Protocols, Unsanitary Conditions, and Severe Isolation as COVID-19 Ravaged California State Prisons

See here for full report.

To date, conditions in California state prisons have been framed largely as individual horror stories, or the inevitable outcome of an unprecedented emergency. Both of these characterizations miss the mark. Researchers from the Prison Accountability Project at the UCLA School of Law analyzed hundreds of calls and letters from people in the custody of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR). The results paint a damning portrait of conditions: incarcerated people were subjected to extreme and sometimes intentional harm, and abuses were not one-off events. To the contrary, the Prison Accountability Project documented routine medical abuse, unsanitary conditions, and physical violence directed at incarcerated people.

After analyzing calls and letters from people incarcerated in CDCR facilities during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Prison Accountability Project identified numerous inadequate and abusive medical practices. Nearly half of all respondents described conditions in which social distancing was impossible, and many described ineffective disease management.

One respondent reported that, after asking a nurse to wipe down equipment before checking their vital signs, the nurse and the accompanying correctional officer rebuked, “You all have COVID anyway.”

Incarcerated people who tested positive for COVID-19 were often forced to quarantine in unsanitary, unheated, and unventilated cells that impeded their recovery. According to one person, the cell in which they were isolated was “so cold [it was] impossible to get from under your covers.” In addition to withholding medical care or administering it only when a person’s condition was dire, correctional staff intentionally disregarded policies designed to protect incarcerated people. For example, even after Governor Newsom issued an executive order halting transfers between prisons, incarcerated people noted that inter-facility transfers continued, amplifying the spread of COVID-19 through disregard and mismanagement.

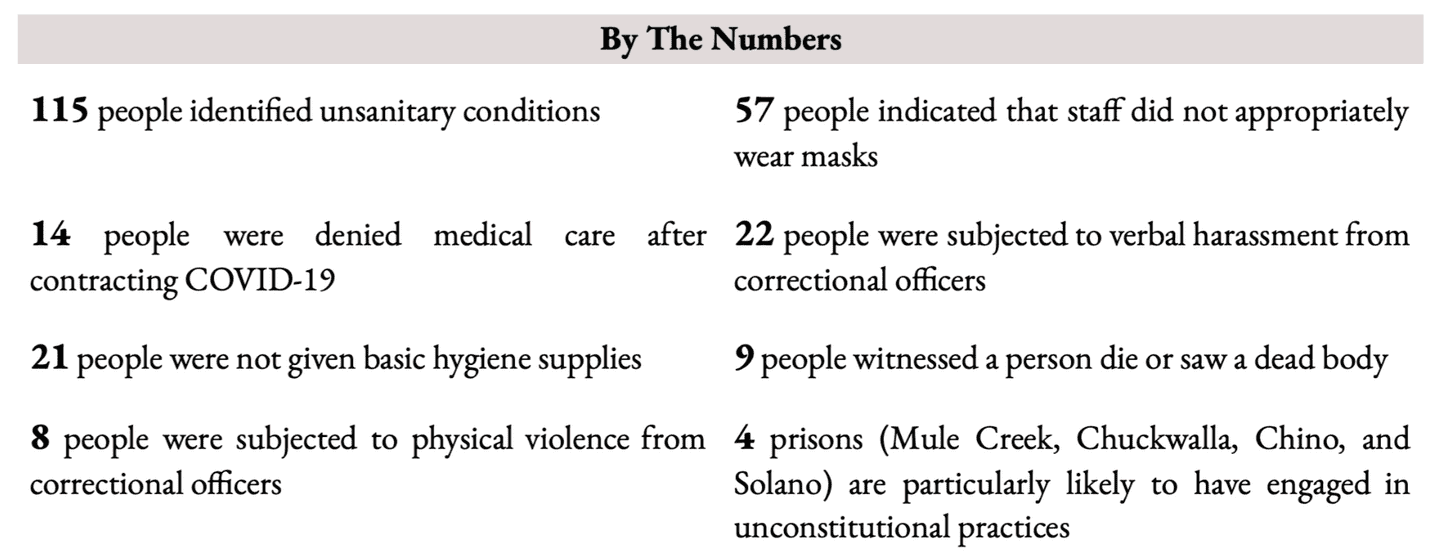

57 respondents indicated that staff members were not complying with mask mandates.

Additionally, correctional staff regularly refused to wear masks around the incarcerated population. Taken together, the conditions discussed by incarcerated people with respect to medical care and disease management were not only inadequate, but abusive.

In addition to medical abuse, incarcerated people were subjected to myriad unsanitary conditions. They were isolated in cells with leaking roofs, mold, and vermin, and in cells that had not been cleaned in between use by infected residents. Discussing their cell, one person noted it “looked like it hadn’t been cleaned in over a year” and seemed to have “rat poop on the floor.” Another person who was being temporarily housed in the prison’s gym reported that the roof was leaking and water was “literally coming through the roof in sheets.” When isolated, many incarcerated people did not have access to basic hygiene or sanitation products. While prisons are unsanitary under the best of circumstances, when confronted with a public health emergency, CDCR facilities were unable to meet even the basic hygiene needs of incarcerated people.

The impact of utterly filthy conditions in CDCR facilities was compounded by extreme isolation. In an effort to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, incarcerated people were routinely isolated in their cells for weeks or months at a time.

Many facilities resorted to using solitary confinement to quarantine incarcerated people infected with COVID-19, with 22 respondents indicating that they were placed in conditions that met the formal definition of solitary confinement.

Restrictions on visitation, programming, and recreation exacerbated the negative effects of isolation and catalyzed serious mental health issues, including depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideations. The rise in mental health issues together with decreased access to prosocial programming fostered increased tension and violence in CDCR facilities, including abuse at the hands of correctional staff and violence between incarcerated people.

In nearly 300 letters, incarcerated people described a pattern and practice of inhumane and abusive behavior that calls into question certain status quo narratives: namely that the CDCR’s pandemic response was an inevitable response to an unprecedented event. Moreover, the trends identified by hundreds of incarcerated people illustrate a pattern and practice of behavior that may constitute cruel and unusual punishment. Medical abuses coupled with unsanitary conditions may demonstrate deliberate indifference to the serious medical needs of incarcerated people—the underlying standard required to prove an Eighth Amendment medical care claim. And intentional, unprovoked physical abuse may form the basis of cognizable excessive force claims under the Eighth Amendment.

Incarcerated peoples’ concerns are too often ignored and unanswered, and the ultimate narrative emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic is no different. If we take seriously the overarching trends independently discussed by hundreds of incarcerated people in California state prisons, the takeaway is deeply troubling. In the CDCR’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic, inhumanity, violence, and deliberate indifference to human life were both normalized and hidden behind prison walls—excused in the name of “emergency.” But, as incarcerated people made abundantly clear, an emergency is no excuse for blatant and pervasive inhumanity. It is our hope that this report helps to open a pathway to real accountability, transparency, and legal recourse.

next post

November 16th, 2023 • Catherine Charleston and Sharon Dolovich

COVID Scorecard Update 9: The end of the federal COVID-19 public health emergency marks an alarming decrease in prison accountability and transparency

15 states and agencies have ceased reporting any COVID data at all, leaving only eight remaining.