February 3rd, 2022 • Amanda Klonsky and Hope Johnson

As Omicron Surges in State and Federal Prisons, Incarcerated People Remain Vulnerable

Since the highly contagious Omicron variant began spreading across the United States in December and January, prisons have seen a staggering rise in COVID cases and deaths.

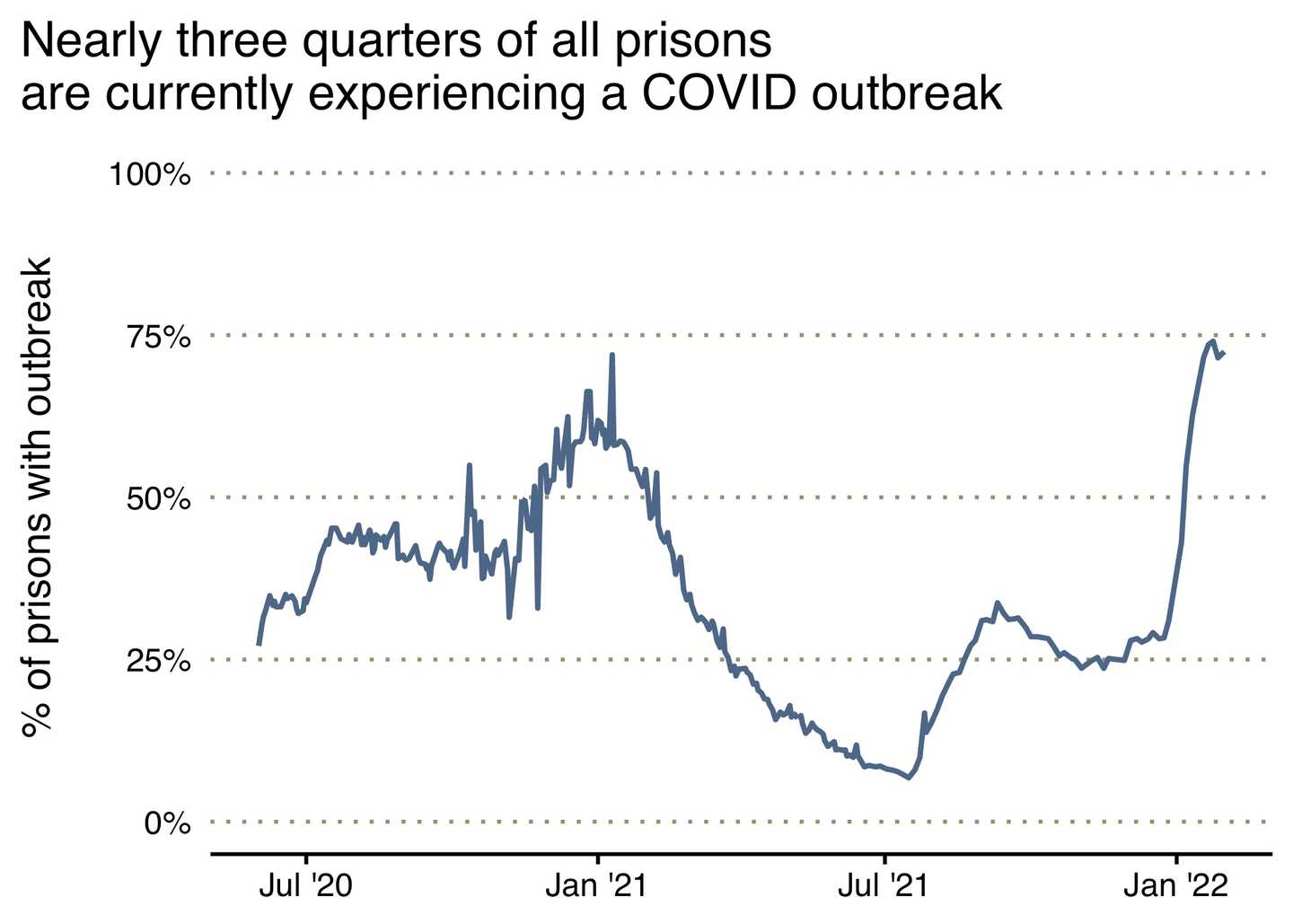

Of the 984 prisons that report data on active COVID cases, 72 percent are currently experiencing an outbreak of at least five people infected among staff and incarcerated people. At least 141 prisons have been in a state of constant outbreak since the first Omicron case was detected in the U.S.

This wave of Omicron infections has been accompanied by a spike in deaths. Since January 1st, 2022, at least 82 incarcerated people have died of COVID – a significant increase compared to the monthly death toll of the previous nine months.

Since December 1st, 15 incarcerated people have died of COVID in Pennsylvania state prisons, 12 have died in Texas prisons, and 8 in New York prisons. Nine incarcerated people have died in Michigan state prisons, six more in Connecticut, four in Wyoming, and three incarcerated people have died in Utah prisons.

During the same period of time, at least 29 prison staff members have died of COVID, including 12 in Texas, four in Maryland, and four in New York.

As we enter the third year of the pandemic, efforts to control COVID outbreaks in prisons are proving plainly insufficient. Congregate settings like prisons have proven time and again to provide the ideal environment for rapid viral spread. In these crowded institutions, social distancing is difficult or impossible, ventilation is poor, and protective practices like masking and even basic handwashing with soap are still not easily available to incarcerated people.

Research demonstrates that vaccine boosters provide robust protection from severe disease, yet few prison systems appear to be offering the booster shot to incarcerated people or staff. Just seven states are reporting data on the provision of booster shots to incarcerated people.

The surge in COVID infections and deaths has exacerbated existing staff shortages in prisons across the United States, and as a result, people who live or work in understaffed institutions now face increasing levels of danger and instability. At Lee Arrendale State Prison in Georgia, only six to seven guards showed up for work each day in a prison holding 1,200 people. Several Georgia prisons report that more than 70 percent of their staff positions are unfilled. Such severe staffing shortages endanger incarcerated people and can make it difficult for prisons to provide basic necessary services such as security, meal distribution, medical care, sanitation, transportation, or access to visitation and movement within prisons.

__

Below, we highlight prisons systems in which we have identified particularly devastating ongoing outbreaks. It should be noted, however, that, even as case numbers surge and, in some localities, hit record numbers, many systems are not reporting complete data regarding COVID in their facilities, and some are reporting even less than they did at earlier points in the pandemic. Florida and Georgia, for example, stopped reporting all COVID-related data in June of last year.

Federal Prisons

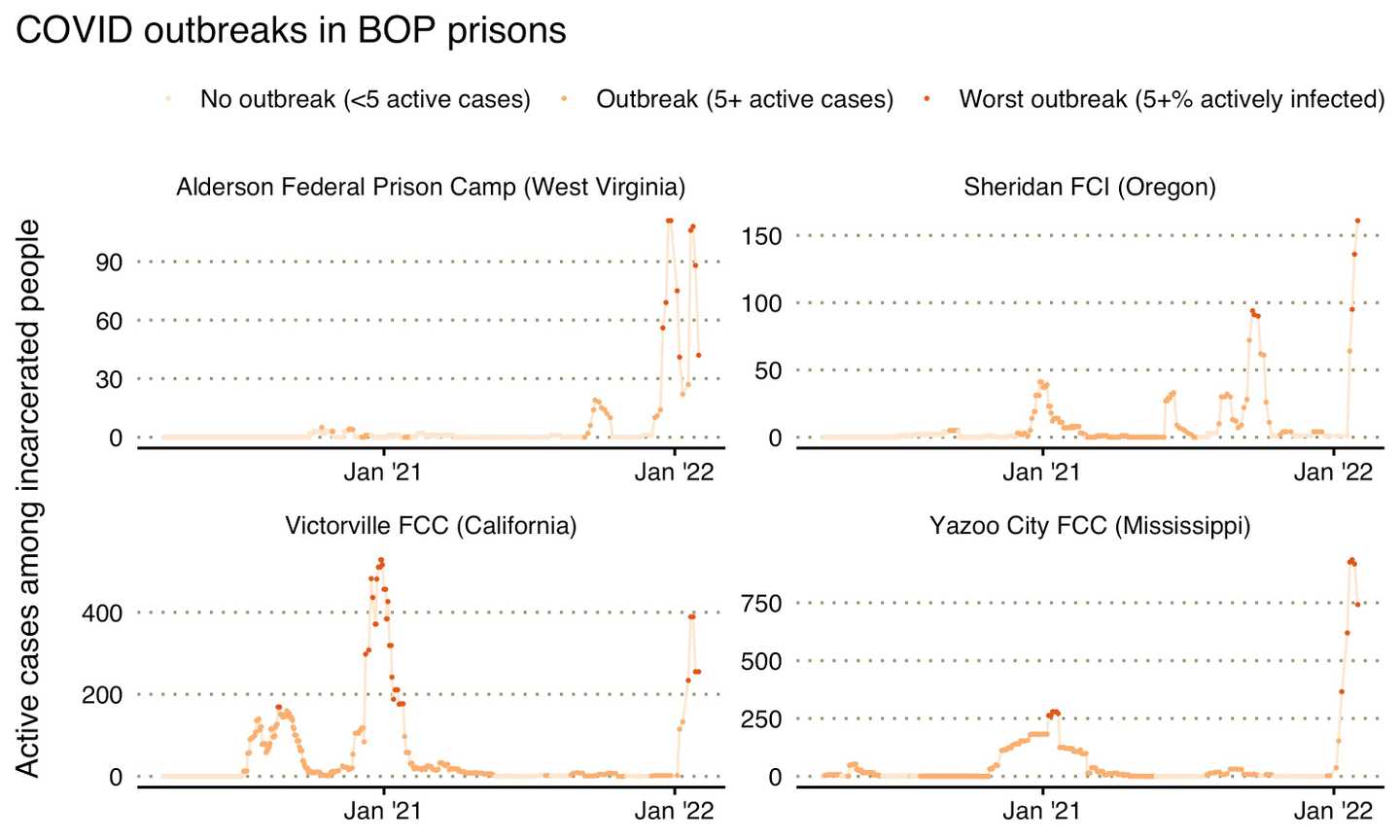

The Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP), with its sprawling system of more than 120 prisons across the country and nearly 150,000 people in its custody, has seen some of its highest case numbers yet. On January 23, the agency reported – for the first time ever – more than 10,000 active COVID-19 cases among people in its prisons.

The agency has also reported an alarming uptick in deaths among incarcerated people. Since December 1, 15 incarcerated people have died in BOP custody, including one individual each at Lewisburg United States Penitentiary and Loretto Federal Correctional Institution in Pennsylvania, one incarcerated person at the Beaumont Federal Correctional Center, two people at the Fort Worth Federal Medical Center in Texas, and three people at the Butner Federal Correctional Center in North Carolina. In addition, another two incarcerated people have died in the Coleman Federal Correctional Center in Florida.

There has also been one new BOP staff death at the United States Penitentiary in Atlanta, Georgia.

State Prisons

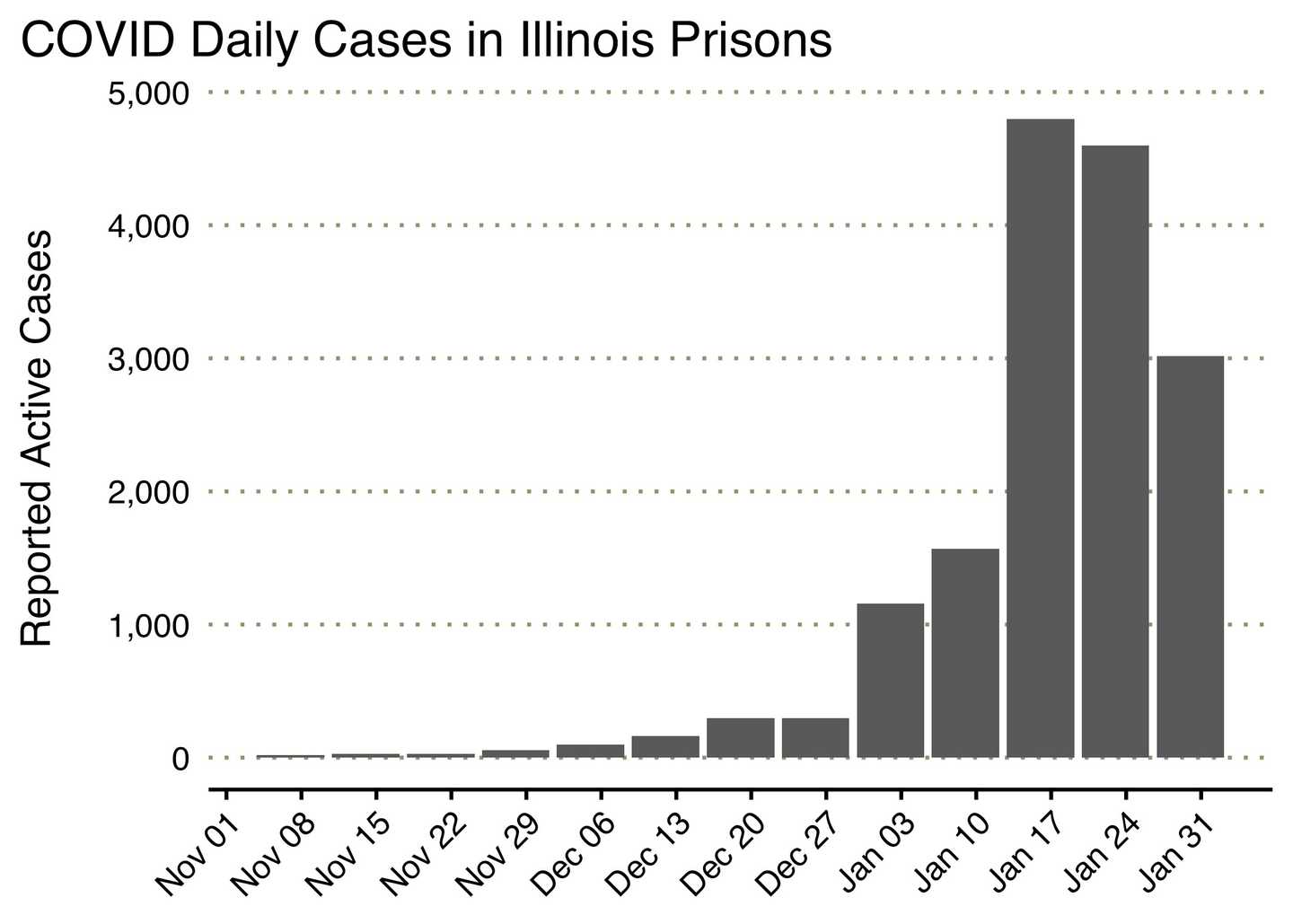

Over the past several weeks, Michigan, California, and Illinois have seen the steepest rise in reported COVID cases based on the percentage of the population with an active infection. At least 15,318 people in California prisons, 10,158 people in Illinois prisons, and 5,946 people in Michigan prisons have reportedly tested positive for COVID since December 1, 2021.

Michigan

The Michigan Department of Corrections (MDOC) recently reported a significant uptick in active COVID cases among the people in its prisons, where the active case count has now reached 6,085. For example, over the past two weeks alone, the number of active cases at the Cooper Street Correctional Facility increased from 12 to 591 cases.

A simultaneous increase in COVID infections among MDOC staff has escalated an already existing staffing crisis in the Department. At Women’s Huron Valley Correctional Center, at least 635 staff members contracted COVID between December 1st and January 31st, a 134 percent increase. At Alger Correctional Facility, the number of COVID cases among staff climbed to 431 from 205 in those two months, a 110 percent increase.

These are just two examples; staff outbreaks are happening across the state. To address staff shortages, the MDOC has now identified ten state prisons in which staff can return to work five days after testing positive for COVID, even if they are still experiencing symptoms. According to reporting from the Detroit Free Press, staff can return to work while experiencing symptoms that include a temperature up to 100.4, nasal congestion, a “non-productive cough,” fatigue, sore throat, headache, and loss of the sense of taste or smell. The choice to allow people who are symptomatic and infectious back to work, likely driven by the urgent need to maintain staffing levels, will make efforts to contain viral outbreaks in prisons even more difficult.

While MDOC staff members who return to work while sick are required to wear KN95 masks, most incarcerated people do not have access to these high-quality masks at this time. According to the Detroit Free Press, incarcerated people are required to wear cloth masks, demonstrated to be less effective than KN95 or medical masks, and it’s unclear how often those are distributed or how (or if) they are sanitized.

In the same period for which the MDOC is reporting thousands of new active COVID cases among incarcerated people, the MDOC has reported an unprecedented decrease in their cumulative COVID case count in a number of its facilities. We have seen the reported number of cumulative cases, a number that should only remain the same or increase, drop in several prisons. These include the Chippewa Correctional Facility, Bellamy Creek Correctional Facility, and Muskegon Correctional Facility, among others.

As a consequence, while active cases statewide are rising sharply, reaching their highest point in more than a year, the reported statewide cumulative count has grown much more slowly. At the end of January, MDOC reported more than 6,000 active cases, an increase of nearly 5,000 since the state reported 1,111 active cases on January 2. In that same time, however, the number of cumulative cases reported by the agency has increased by just 2,679.

The department has not provided any explanation as to what reporting changes could have caused the cumulative case count to decrease while the number of active cases has risen by thousands.

California

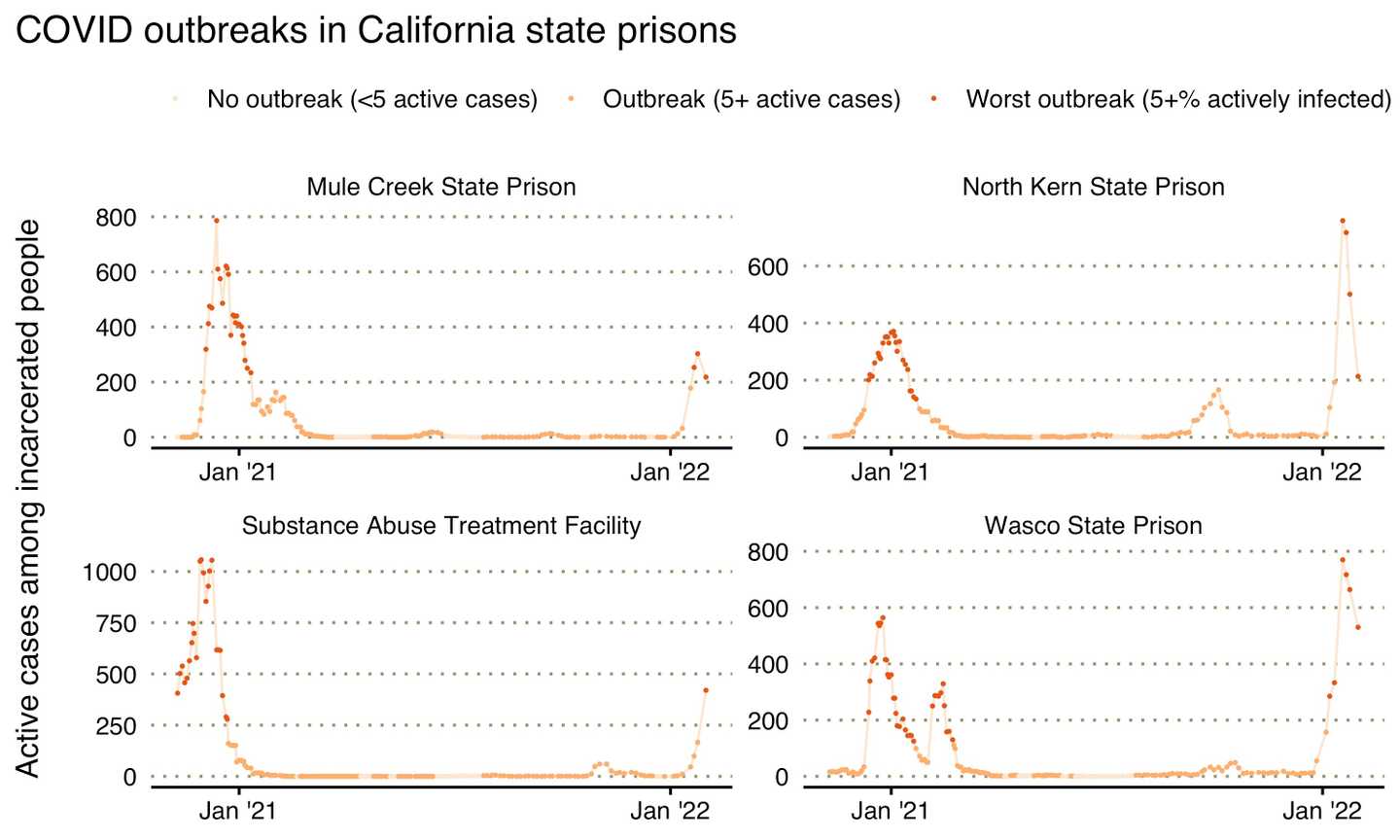

California’s North Kern and Wasco State Prisons are seeing their largest COVID outbreaks yet. 530 people are currently infected at Wasco State Prison Reception Center, where at least one incarcerated person died of COVID since the end of December 2021. Additional outbreaks are ongoing at North Kern State Prison, Mule Creek State Prison, California Institution for Men, and Folsom State Prison, with hundreds of people infected in each facility. Wasco State and North Kern were also the sites of large outbreaks during the Delta variant surge in October 2021 that left hundreds of people infected at each prison.

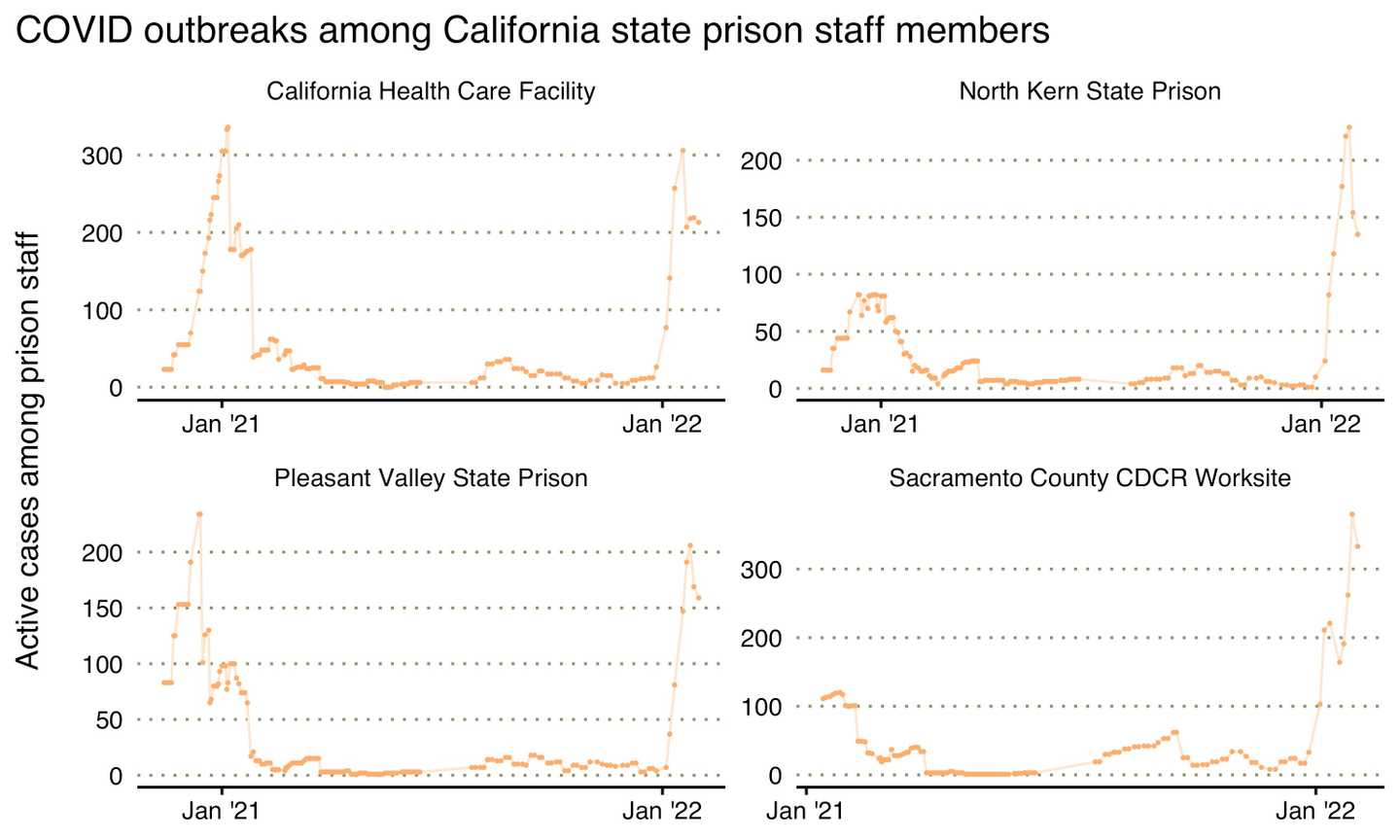

Infection among prison workers is also escalating the staffing crisis in California prisons. At least 14,507 people who work for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) have tested positive for COVID since December 1st, 2021. According to recent reporting from Davis Vanguard, CDCR has about 3,000 vacancies statewide. These staffing shortages impact the Department’s ability to provide basic care and safety for incarcerated people amidst a broader public health crisis. People in California prisons have reported being unable to receive mail or commissary packages, lost yard time, and been denied other services as the result of staffing shortages.

Illinois

From the beginning of December 2021 until the end of January 2022, 10,158 incarcerated people and 3,888 staff in the Illinois Department of Corrections (IDOC) were infected with COVID. The massive COVID outbreak across Illinois prisons has included a surge of 1,152 new cases in the Menard Correctional Center, 849 new cases at the Western Illinois Correctional Center, and hundreds of new cases among staff and incarcerated people at Stateville Northern Reception and Classification Center.

While cases have been surging in Illinois prisons, vaccination and booster rates remain low among IDOC staff. While 75 percent of incarcerated people in Illinois have been vaccinated, by late December, just 65 percent of IDOC staff had gotten the vaccine. Only about seven percent of IDOC staff have gotten a third dose or “booster shot,” and just forty-five percent of people incarcerated in Illinois prisons have received a booster shot.

In August of 2021, Governor Pritzker issued a vaccine mandate for IDOC employees, but this order was challenged by the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, the primary union for corrections officers. The mandate was recently upheld in court, and all IDOC employees are now required to have their first dose of the vaccine by the end of January. It is urgent that prison agencies across the country prioritize incarcerated people and staff for vaccine boosters, especially as we anticipate the emergence of the next COVID variant.

Preparing for the Next Wave

State and federal prisons are once again the sites of some of the largest COVID outbreaks in the United States. For two years, the consensus among national health and safety experts has been that large-scale decarceration is required to protect public health and prevent mass outbreaks in carceral settings. In the early days of the pandemic, some systems took limited steps to reduce the number of people in their prisons; these measures were commendable but insufficient. The crowded conditions, poor ventilation, lack of access to PPE, and low rates of vaccination in prisons and among staff set the stage for yet another wave of widespread infection during the Omicron surge. Furthermore, research demonstrates that the ongoing failure to protect incarcerated people from the virus contributes to the spread of COVID in surrounding communities.

As the United States faces continued outbreaks and the potential emergence of new strains of the COVID virus, state and federal agencies must double down on efforts to control outbreaks in carceral settings. In this period of emergency, jurisdictions should make every effort to reduce the number of people behind bars, and to release anyone who is particularly vulnerable to infection or death from COVID. Continued efforts at mass vaccination– including vaccine mandates for corrections staff, and booster shots for both staff and incarcerated people– are essential to gaining control of the pandemic. The expansion and improvement of carceral health care are required to prevent unnecessary deaths among incarcerated people. Until these steps are taken, prisons will be sites of mass COVID outbreaks, endangering the lives of incarcerated people, staff, and all those who live in surrounding communities.

next post

February 7th, 2022

Omicron Behind Bars (1/31-2/4)

The Omicron variant is causing enormous, in some cases unprecedented, surges of COVID behind bars. Here's what we saw last week.