November 4th, 2022 • Amanda Klonsky, Neal Marquez, and Lauren Woyczynski

Jails Should Be Prioritized for Surveillance of New COVID Variants

U.S. jails have repeatedly been the sites of some of the largest and fastest-spreading COVID outbreaks in the world. The close living quarters, poor ventilation, and constant flow of people make jails ideal incubators for this highly contagious virus. Outbreaks in jails do not remain behind jail walls. Significant population churn and staff that enter and exit every day bring the virus from jails to local communities and back. One study found that, in the early months of the pandemic in 2020, the cycling of people through Cook County Jail was associated with 15.9% of all documented COVID cases in Chicago and 15.7% of those in Illinois. As a result, the deadly public health consequences of jail incarceration—and poor management of the virus inside jails—are a threat to public health more broadly.

A key component of public health efforts during the pandemic has been understanding new variants of the virus—their characteristics, prevalence, and spread. Genomic sequencing is an important piece of data that public health researchers use to understand how disease spreads, inform our pandemic preparedness, and predict how the virus might exist and spread in the future. In spite of their importance as sites of rapid transmission, jails still are not being prioritized as sites of increased surveillance for new COVID variants.

As we approach winter, public health experts are once again expecting a surge in cases nationwide as new immunity-evasive Omicron subvariants continue to emerge and take hold. Public health officials fear a potential strain on hospital systems could come from even a small increase in COVID hospitalizations alongside increased hospitalizations for influenza and RSV (two other respiratory viruses that will also circulate in our country’s carceral facilities this winter). In the face of new and highly contagious COVID variants, genomic sequencing in jails could prove to be an important strategy for preventing mass outbreaks this winter, both in jails and beyond their walls.

Comparing COVID Outbreaks in Jails and Surrounding Communities

When looking back on the last major Omicron surge in jails and their surrounding communities at the end of 2021, we noticed a worrisome trend. In at least three large jails – Cook County, Illinois; Maricopa County, Arizona; and Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania – widespread COVID outbreaks began in county jails during periods of low community spread outside of the jail, and significantly before local departments of public health had observed the presence of Omicron in their counties. In two cases, these jail outbreaks began several weeks prior to the record-high Omicron outbreaks of late 2021 that occurred outside the jail walls.

To make sense of these early and rapidly spreading outbreaks in Cook County, Maricopa County, and Philadelphia jails, we need more information. When we last inquired about protocols, we found that jails do not generally send out COVID test samples for genomic sequencing — so it is impossible to know which variant drove these spikes. Were the late November 2021 outbreaks belated Delta outbreaks that took place while community spread was otherwise low? Or were these early Omicron outbreaks, with the new variant emerging in the jails before departments of public health were aware of its presence in the community? Would monitoring these jails for new variants of concern have resulted in earlier awareness of Omicron in the surrounding communities? Each of these scenarios has important public health implications, but without closer monitoring of COVID in jails, we will never know enough about variants to plan and implement interventions that could protect people in jails and surrounding communities.

In recent weeks, we’ve identified significant increases in COVID cases in a number of carceral settings around the country, including the Maricopa County jail and ICE’s Karnes Family Detention Center in Texas. However, we’ve also found a steep dropoff in transparency this year; 21 prison systems no longer report even basic data on the number of active COVID cases in a facility. Since January 2022, nine prison systems have stopped reporting active COVID cases. Throughout the pandemic, consistent COVID data reporting from jail systems has been even harder to find. Without these baseline data, the public won’t know whether last winter’s trends occur again.

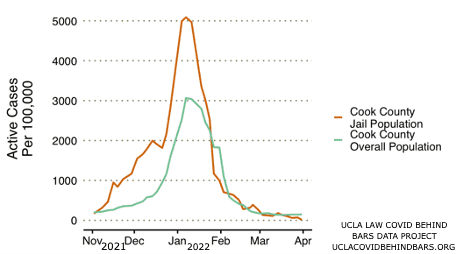

COOK COUNTY COUNTY JAIL

Starting in early November 2021, the number of COVID cases in the Cook County Jail in Chicago began climbing steadily upward, reaching a positivity rate of 1% (1,000 cases per 100,000 people) on November 23. The outbreak peaked with a positivity rate of over 5% on January 7, 2022, the jail’s highest positivity rate to date.

In the early weeks of the Cook County Jail outbreak, however, COVID case rates remained relatively low in the surrounding community. On November 23, when the positivity rate had climbed to 1% in the jail, it was just 0.35% in the county as a whole. Cook County did not reach the 1% threshold until late December, more than a month after the jail did. This higher positivity rate could be a reflection of the testing regimen; however, the rapid and earlier rate of change in the jail versus the community may also indicate that the Omicron variant was already circulating in the Cook County Jail long before it was identified in the broader community. The Illinois Department of Public Health and the Chicago Department of Public Health first noted Illinois’ first Omicron case on December 7, 2021. By then, the spike in COVID cases inside the Cook County Jail had been steadily rising for a month, while the community outbreak was increasing much more slowly. If the Cook County Jail had been a site of surveillance for new COVID variants, it is possible that public health officials would have identified Omicron in Illinois weeks earlier.

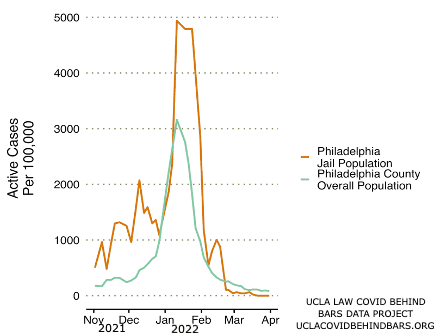

PHILADELPHIA COUNTY JAIL

The Philadelphia Jail offers another example. The Omicron outbreaks in the Philadelphia Jail and in the community peaked at the same time, with the peak of the surge for both occurring on January 11. However, COVID cases in the Philadelphia jail started rising well before community rates of infection began to rise. The Philadelphia Jail reached a reported positivity rate of 1% (1,000 cases per 100,000 people) as early as November 19, 2021, whereas COVID rates in the broader community remained below this threshold until January 4, 2022.

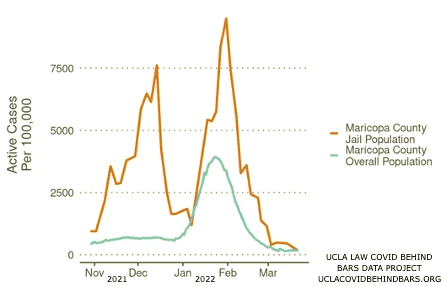

MARICOPA COUNTY JAIL

Maricopa County Jail saw two large COVID surges this past winter, one in late 2021 and the other in early 2022. The first outbreak peaked on December 14, 2021, at a case rate of 7.6% (7,610 cases per 100,000 people).

Maricopa County as a whole entered a COVID surge several weeks later. Outside of the jail, the Omicron outbreak began in early January and peaked on January 24, 2022, at a case rate of 3.9% (3,900 cases per 100,000).

Maricopa County Jail experienced a second, larger, surge around the same time as the rest of the county, with a spike peaking on January 31 at a case rate of 9.5% (9,510 cases per 100,000 people).

Understanding What to Measure and What Information It Unlocks

Genomic sequencing, which allows the classification of a COVID infection as caused by a particular variant and lineage, has been a key component of public health efforts during the pandemic.

According to the CDC, genomic sequencing is an important strategy for characterizing the virus, estimating a particular variant’s prevalence, and investigating the spread of a variant in outbreaks.

With increased lab capacity, jail administrators could use genomic sequencing to track variants in real time and use this information to inform mitigation tactics. Knowing the prevalent variant in a local jail may also shape public health officials’ broader community planning decisions. For example, it may be more important to decarcerate, to emphasize masking, or to shift visitation or programmatic policies, depending on the nature of the current variant. Collecting this information will also give public health officials the tools to include the incarcerated population in our future public health planning and advocacy.

Genomic sequencing can be employed to track the spread of the virus at a high level, without the detailed surveillance required for contact tracing. Sequencing would aid in understanding precisely how certain variants are traveling between carceral settings and the community. Furthermore, public reporting when new variants emerge in jails would add an important layer of data transparency from these facilities, particularly at a time when many jurisdictions have stopped publicly reporting COVID data.

Instead of declaring the pandemic over and backing off of the measures that protect our communities, such as testing and publicly reporting COVID data, jails should be sites of increased surveillance and study, where public health techniques like genomic sequencing are prioritized. Focusing on these potential incubators and precursors of COVID surges, public health officials can intervene to protect the vulnerable, advancing our understanding of the variants that are threatening our communities.

next post

November 29th, 2022 • Amanda Klonsky and Neal Marquez

Study: Hispanic People in Texas Prisons Died of COVID at a Rate Double Their White Peers, Black People Died at Rate 1.6 Times

A New Study from UCLA finds that Hispanic People Died of COVID at Twice the Rate of their White Peers, and Black People Died at Rate 1.6 Times. Prison Crowding and Medical Copays Could Be Driving These Disparities.