November 29th, 2022 • Amanda Klonsky and Neal Marquez

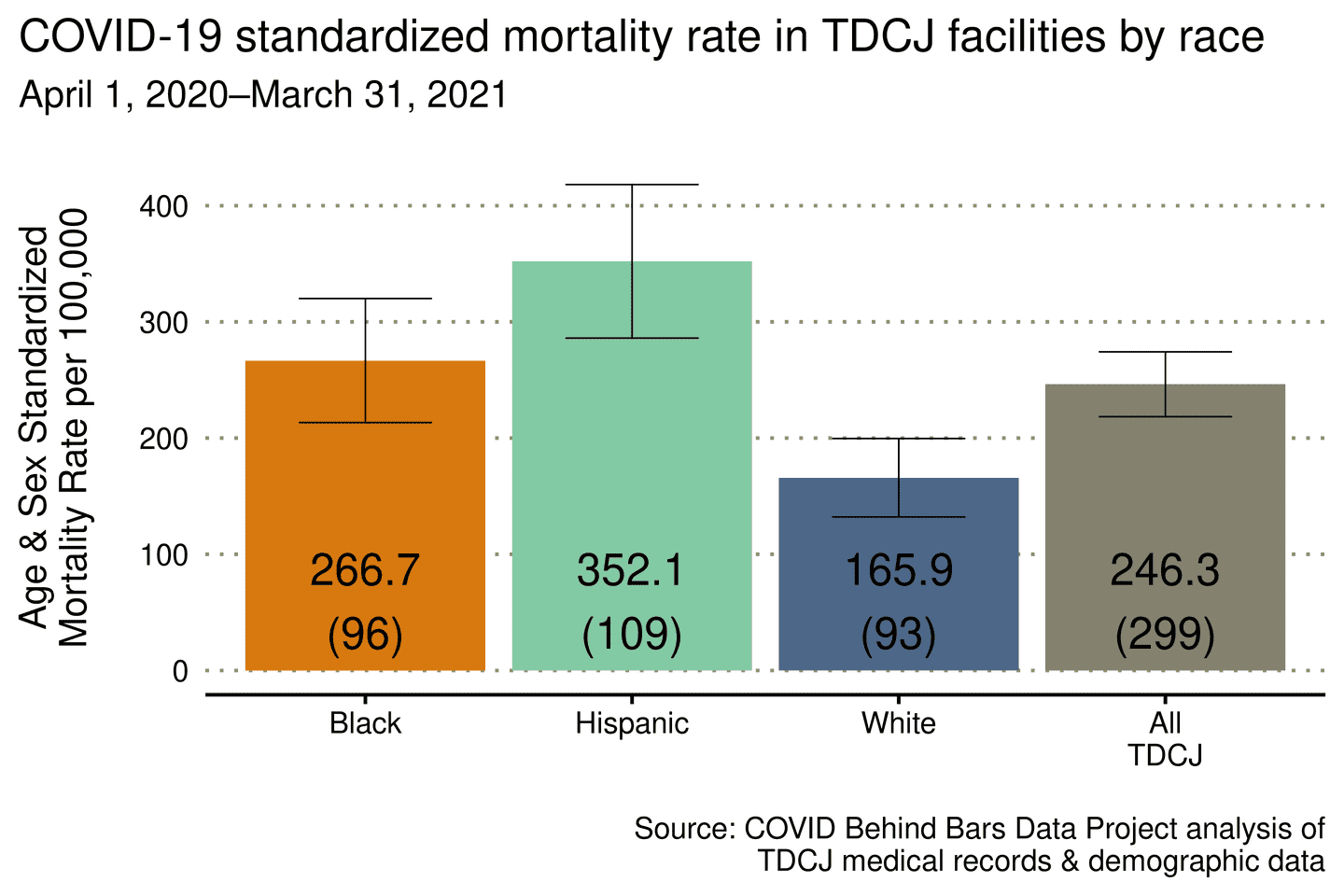

Study: Hispanic People in Texas Prisons Died of COVID at a Rate Double Their White Peers, Black People Died at Rate 1.6 Times

A PDF of our press release for this publication is available here.

Our new study, published in Health Affairs, found that Black and Hispanic people in Texas prisons died of COVID at significantly higher rates than White people. In the first year of the pandemic (April 2020 - March 2021), Hispanic people in Texas prisons died from COVID at twice the rate of White people incarcerated in Texas. The rate of mortality for Black people was 1.6 times that of White people in Texas prisons.

The Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) has higher incarceration rates for both Black and Hispanic populations relative to the White population, which reflects the pattern of incarceration in prison systems across the U.S. The TDCJ has also had high rates of reported COVID infection, which made this an important place for us to start our study. Outside of the Bureau of Prisons, which is the federal prison system, Texas has the largest prison population in the U.S. The Project intends to replicate this study with 20 other state prison systems for which we have been able to collect the necessary data.

Our study also found a reversal in previous, all-cause mortality trends. In the 12 months prior to COVID, White all-cause mortality rates were higher than those for Black and Hispanic people in Texas prisons (although these differences were not statistically significant). In the first year of the pandemic, however, Hispanic and Blacks all-cause mortality rates were 1.22 times higher than White all-cause mortality rates.

Although racial health disparities in COVID mortality have been identified outside of prisons, this is the first study to examine these disparities behind bars – and to begin to identify some of the potential drivers. The UCLA COVID Behind Bars Data Project is interested in understanding the ways that structural racism impacts health outcomes for people in prison.

We know that Black and Hispanic populations in the United States have higher rates of incarceration, as well as higher rates of police interaction, and more punitive bail decisions, sentencing, and parole outcomes as compared to the White population. Racial bias permeates every aspect of the U.S. criminal legal system and the collection of data on the impact of COVID on incarcerated communities is essential for furthering health equity and racial justice in the United States.

What could be driving these racial disparities in mortality outcomes?

THE PRISONS WITH THE HIGHEST BLACK AND HISPANIC REPRESENTATION WERE ALSO THE MOST CROWDED.

In our exploratory analysis, we found that the Texas prisons that are predominantly Black and Hispanic have a higher population density (i.e., they are more crowded) than the prisons that are predominantly White. Prison population density is a known risk factor for the spread of COVID. Public health and legal scholars have long urged prison systems to reduce their populations to reduce the risk of COVID transmission. More investigation is needed here to relate prison density to COVID transmission; however, the relationship between higher population density and higher COVID transmission in carceral settings has been demonstrated.

PREVIOUS RESEARCH HAS FOUND RACIAL DISPARITIES IN ACCESS TO HEALTHCARE IN PRISONS.

People incarcerated in Texas are required to pay co-pays for medical visits. Previous research had found that healthcare access in prisons is stratified by race. One reason for this stratification is that people of color in prison are often more reluctant to seek medical attention due to co-pays that prisons charge for medical attention, as compared to White people, who may have more ability to pay. Many state prison systems have abolished medical copays for those who are incarcerated, but Texas continues to charge $13.55 per visit, the highest cost among state prison systems. While the TDCJ did temporarily suspend medical copays for those “exhibiting COVID or flu-like symptoms” during the start of the pandemic, COVID has a range of symptoms. Without assurance that the costs of a medical visit would be covered, many incarcerated people may have been reluctant to seek medical care. What’s more, in 2021 TDCJ reinstated medical copays even for those with COVID or flu-like symptoms.

PRE-EXISTING CONDITIONS ALONE DO NOT EXPLAIN THESE DISPARITIES.

Pre-existing chronic diseases increase the risk of COVID mortality for people who become infected. If the Hispanic or Black populations had a higher prevalence of pre-existing conditions we should expect to see higher rates of COVID mortality for these groups within the TDCJ. However, when examining the age-standardized prevalence of conditions related to COVID mortality, a previous publication found that most of these chronic conditions are higher among the non-Hispanic White population in Texas prisons than among the Hispanic population. While the age-standardized prevalence of diabetes was higher for Hispanics, all other conditions in the study had a higher age-standardized prevalence among the White population, including ischemic heart disease and hypertension, which are known risk factors for COVID mortality. Black populations had higher rates of pre-existing conditions or comparable rates of pre-existing conditions compared to White populations.

COVID mitigation efforts in carceral settings should include strategies that consider and address racial inequities.

- VACCINATION AND DECARCERATION

Decarceration and vaccination are two of the most effective measures for reducing the mortality burden of COVID within carceral settings. We call for expanded access to vaccines and boosters for incarcerated people. Vaccination strategies must anticipate and address possible differences in uptake across race and ethnicity. We are also among the broad consensus of public health experts who call for mass decarceration. An urgent priority of population reduction efforts should be the release of vulnerable people, including the elderly and those with chronic health conditions who are most at risk of death from COVID.

- END MEDICAL CO-PAYS

Together with many other scholars and public health experts, we call for the removal of medical co-pays which can inhibit incarcerated people from utilizing health care in prison, and from seeking early protective care related to symptoms of COVID.

- EXPAND DATA TRANSPARENCY

Many jurisdictions across the US are no longer reporting COVID information. We call for an expansion of data reporting and transparency in the TCDJ and across carceral systems, especially including data stratified by race and ethnicity, and data about the prevalence of pre-existing conditions. This data is critical to protecting vulnerable populations in jails and prisons, including the elderly. Nearly 150,000 people incarcerated in state prisons were 55 or older in 2016, the most recent year for which this data is available, while more than 20,000 people in federal prisons are 56 or older, according to Bureau of Prisons data.

- ADVANCE SCHOLARSHIP ON RACIAL DISPARITIES IN PRISON HEALTH OUTCOMES

We hope that more scholars will take up this line of inquiry. We recognize that we’ve raised more questions than we have answered and that further investigation into these racial disparities is necessary. For public health efforts to be effective in combatting the pandemic, we need a widespread analysis of racialized health disparities in carceral settings. We urge other scholars and public health agencies to pursue this line of inquiry with us.

Beyond the fundamental racial disparities in arrests and sentencing, our study suggests that Black and Hispanic people are facing disparate conditions behind bars that make them more vulnerable to death from COVID infection – including prison crowding and differences in access to health care. These racially disparate and inhumane conditions contribute to many negative outcomes both inside carceral settings and in their surrounding communities. The economic and epidemiological impacts of the pandemic are exacerbated by racial inequities which keep some groups behind bars longer, under more crowded conditions, and with less access to healthcare. As public health agencies seek to reduce risk to local communities, families, and people behind bars, these inequities must be addressed. As the nation attempts to move on from the pandemic, we should not forget the nearly two million people behind bars, who remain among the most vulnerable to COVID infection and death.

next post

January 13th, 2023

A Global Crisis: Our Q&A with Dr. Joe Amon on the International Crisis of COVID Behind Bars

We spoke to the health and human rights expert about the impacts of COVID on incarcerated people around the world, poor data transparency by just about all countries, and the potential for a new UN treaty requiring better data collecting and reporting.