September 1st, 2021 • Marjorie Naila Segule

The Vaccine Rollout Is Leaving Behind Incarcerated Children

The recent rise of the Delta variant across the country has fueled what, for many, has been a nightmare scenario: a pandemic among children. The number of children hospitalized with COVID-19 across the country is higher than it has ever been and the trend is showing no signs of slowing.

The good news is that more children are being vaccinated. Kids older than 11 years old are currently authorized to receive COVID-19 vaccines and, in increasing numbers, are. But so far, the vaccine rollout among American youth seems to have neglected one group of especially vulnerable children: those in detention or prison.

Children in detention and prison are at high risk for COVID-19 infection, and high risk for health complications if infected. There have been more than 5,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 among youth in detention facilities across the United States, a population that has higher rates of asthma, a risk factor for health complications. This population of children also faces considerable gaps in Medicaid coverage, suggesting a higher likelihood of untreated pre-existing conditions.

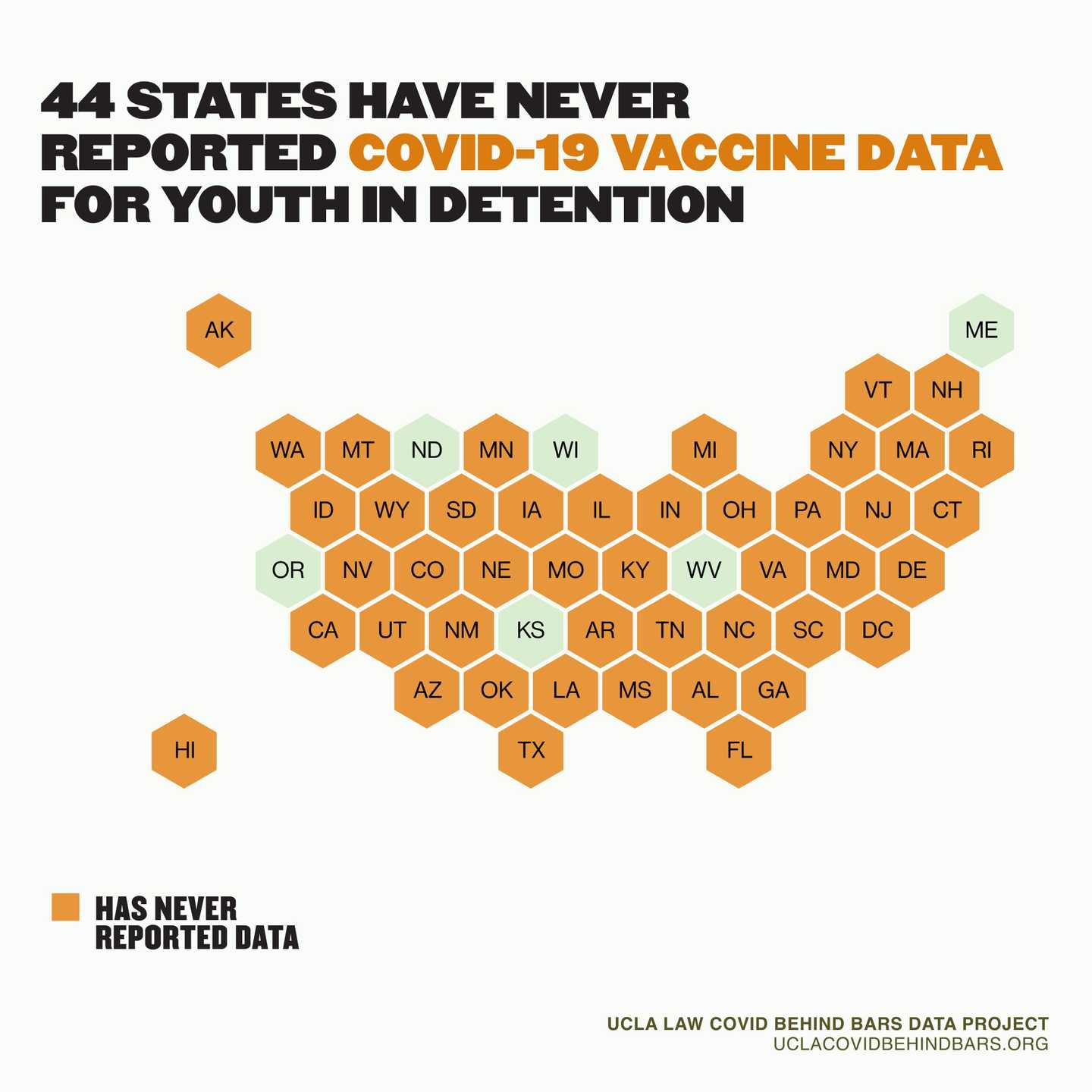

It is hard to know just how many children in confinement have — and have not — been vaccinated across the United States. So far, only six states (Kansas, Maine, Oregon, Wisconsin, North Dakota, and West Virginia) have published any vaccination numbers for their youth in detention, and those numbers are generally very low. According to its own reports, North Dakota has not vaccinated a single child in detention. In Maine, just 28.6 percent of children in detention are fully vaccinated. In West Virginia, about 40 percent have been fully vaccinated.

It’s likely that other states are vaccinating children in detention but are not publishing data on it. For example, New York’s Office of Child and Family Services announced its intention to prioritize vaccinating incarcerated youth in February. They still, however, have not published any public metrics data showing that they actually have started vaccinating.

But transparency is absolutely critical here: when juvenile justice agencies don’t publish their COVID-19 vaccine data, it is all but impossible for the public, including for public health authorities and families, to assess the risk children face while incarcerated. It also becomes impossible for the public to hold agencies accountable for protecting the children in their custody.

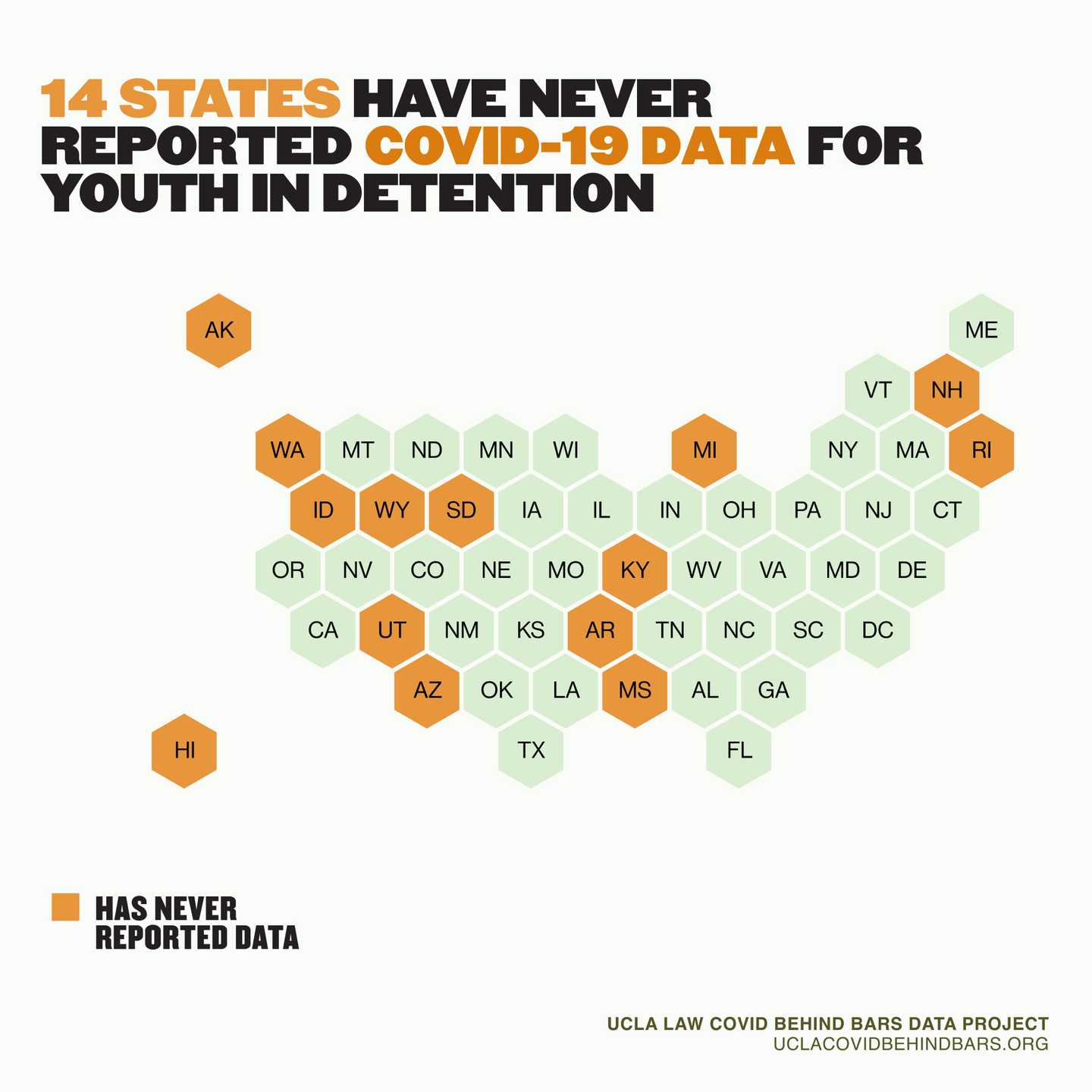

Such data gaps are not new: state agencies have failed to report basic health data about the children in their custody throughout the pandemic. Since the public health crisis started, 14 states have not reported any COVID-related health data at all concerning the children in their custody. Similar to agencies overseeing adult incarceration, some juvenile justice agencies have stopped reporting new data since June and have even removed their historical COVID-19 data. Florida and South Carolina have both rolled back their transparency measures despite recent surges in cases statewide and nationally and suspended or restricted visitation in these facilities.

These data gaps often even pre-date the pandemic. Because of broader and longstanding gaps in data concerning juvenile detention even in “normal times” – including data as basic as the total numbers of children held in custody in each system and across the country – in some states, we cannot calculate total COVID-19 positivity rates among children in custody, nor estimate how many children have yet to test positive but remain vulnerable, even when COVID data is reported.

Further, because there is so little reporting on the vaccination rate of staff in juvenile facilities, we cannot know how many – or few – staff interacting with children in state custody have been vaccinated. There is reason to be concerned, however, that those rates are low: in West Virginia, only 37% of juvenile services employees have been vaccinated on-site (there is no data on off-site vaccinations). Across the country, vaccine acceptance rates among prison staff have been concerningly low and politicians have been generally reluctant to apply vaccine mandates to prison staff.

Even before the slow vaccine rollout, the pandemic made children in custody even more vulnerable to health and safety risks, including related to their mental health, as well as general development. Detaining young people, even without stricter lockdown measures, dramatically increases their risk of self-harm and the long-term incidence of suicide, well into adulthood. Most children in detention — a category that in some jurisdictions includes children as young as 10 years old—have been unable to have in-person visitation. Those who have been able to return to in-person visits are often unable to hug their family members due to no-contact visitation. Many have been unable to return to in-person schooling, and there are reports of youth missing out on federally mandated therapeutic services and supports to address their learning disabilities or mental health challenges due to restrictions adopted to prevent COVID spread.

During the pandemic, Black and Latinx children have been released from juvenile detention centers at rates far lower than their white peers, compounding and further re-entrenching racial inequities in juvenile detention systems. Youth of color have also been detained for much longer periods than they were before the pandemic.

Holding young people in detention and separating them from their families — and in doing so, disrupting their development, education, and life trajectory — has always been an ill-conceived practice with severe consequences for the health and safety of vulnerable youth. The pandemic has made it even more clear, however, that youth incarceration is both a moral crisis and a threat to public health.

Juvenile justice agencies are responsible for the care of society’s most vulnerable children and should take all possible steps to honor this public trust, including accelerating vaccination distribution in the midst of a global pandemic. And when they do, they must also provide timely, transparent, and publicly accessible data on vaccination rates for the youth they hold in custody.

next post

September 10th, 2021 • Victoria Finkle and Hope Johnson

The Life or Death Stakes of Partisan Politics Behind Bars

A recent study reveals that federal judges appointed by Democrats were far more likely to grant compassionate release during the pandemic than those appointed by Republicans. But emergency release should be about public health, not partisan politics.